Depression in the diaspora: insights in researching Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in a Ugandan refugee settlement

Daniela Arocha Ramirez

- MARCH, 2023

My first time in sub-Saharan Africa consisted of a trip to Uganda in February 2023. My familiarity with the country only began two months prior to my departure while defining my thesis project in Sweden; therefore, it felt like going from the theoretical to the real world. After spending my first day in the capital city Kampala getting prepped by my supervisor and colleagues, we embarked on a ten-hour road trip to the Northern part of the country, specifically to the district of Lamwo. Our goal was to rest nearby in Kitgum, and then head to Palabek Refugee Settlement (PRS), one of the 13 rural refugee settlements in Uganda, which has mainly been receiving South Sudanese refugees since 2017. It is worth noting that the country has traced a great path, becoming the largest recipient of refugees in Africa and the third largest in the world.

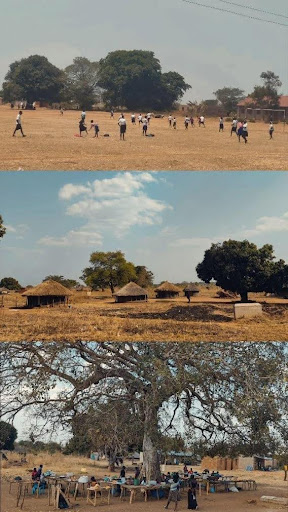

The morning came and we set out on our journey. To my surprise, the entrance to the settlement is barely noticeable. Although there are a couple of signs announcing it, the landscape, people, boda-boda’s, schools, and general forms of organization encountered were not significantly different from the two-hour journey that preceded it. This speaks to the fact that the refugee settlement easily blends into the rest of the community, which may contrast with the picture of refugee camps as seen in other humanitarian situations in different parts of the world. This is ultimately the reflection of the progressive refugee policy for which Uganda has received recognition, where freedom of movement, land allocation, and self-reliance are innovative points that impact the integration of the population.

As a Colombian psychologist with prior experience in the humanitarian sector, I have worked with victims of forced displacement resulting from my country’s internal armed conflict, as well as with refugees from Venezuela. This experience sparked my interest in exploring mental health policies and implementation of Group Interpersonal Therapy for Depression in South Sudanese refugees and displaced affected persons, as part of my European Master’s thesis in Social Work. This treatment is recommended as a first-line treatment approach by the World Health Organization’s Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP).

Previous experiences had led me to empathetically listen to and closely attended to the anguish of individuals who have suffered through traumatic situations of displacement. They often have to leave behind everything they knew, grieve for loved ones lost along the way, and face various vulnerabilities and traumas upon arriving in a host community that can sometimes be hostile. During my time in Uganda, I have engaged in a range of interactions, including conversations, focus groups, and interviews with multiple actors, including beneficiaries, local host community, project managers of the Lutheran World Federation (LWF), district officer, and technical, policy, and mental health experts. Through these interactions, I have realized that although of course there are contextual particularities, the psychological suffering, and consequences of displacement are similar across cultures and regions, as we all share a common humanity.

There is still a way to go in analyzing the information, but for now, I can give some preliminary considerations. One of my main motivations in this topic is to have a look at a therapy that distances itself from westernized individualized forms, in order to observe a therapeutic form in a group and communitarian setting. The benefits of group cohesion have been one of the aspects most highlighted by the beneficiaries, who recognize the improvement in their depressive symptoms such as better sleep and renewed interest in life, valuing the group and asking it to be continued, by additionally raising their voice to request a training in activities that allow them to build and focus on a productive life project.

It was encouraging to see an implementation team that, from the management level to the facilitators in the field, acknowledges and seeks to respond to the challenges involved in working on depression in this community. They invite them to recognize the importance of their mental health needs, while also aiming at trying to ensure that their basic human rights are met, and they remain adaptable while maintaining a stance on international policies that guide their implementation.

However, the challenges and gaps must also be noticed. Despite increases in suicide attempts, alcohol consumption, among other behaviors that evidence depression in this community, mental health continues to be underappreciated. In principle, people go in search of the intervention, hoping to receive an economic or tangible benefit, deceiving about their psychological conditions. This is not surprising, since having a series of unsatisfied human needs, it is a survival strategy to seek to satisfy them by any means. It should also be noted that as long as there are precarious living conditions, the person can return to a depressive state. So, the real question is, how is the policy response filling these gaps?

Uganda, like other low- and middle-income countries, is highly dependent on financial resources from international organizations. The use of international humanitarian guidelines and manuals has also been a constant, but these are beginning to fall short in a country that has passed the crisis phase and needs a mental health development approach with a lens that responds to the context that its innovative refugee policy has created. However, there is a light emerging from the 2018 update of a rather old Mental Health Act, which now targets the provision of mental health treatment at primary health centers, as well as professionals who recognize the value of listening to populations and research for the generation of appropriate tools.

Over the next three months, I will be completing this study, and for now, I can only feel grateful to the study participants in PRS for trusting and opening up their honest views, the management of the COMPASS project, LWF, and the amazing team members of Makerere University’s Centre for Health and Social Economic Improvement (CHASE-i) for their support and guidance in this extraordinary experience. I cannot thank enough my supervisor Dr Gloria Seruwagi who managed to make the road trip to PRS and offer practical insights while in the field.

The writer (centre) with the team from CHASE-I in Palabek Refugee Settlement, Uganda